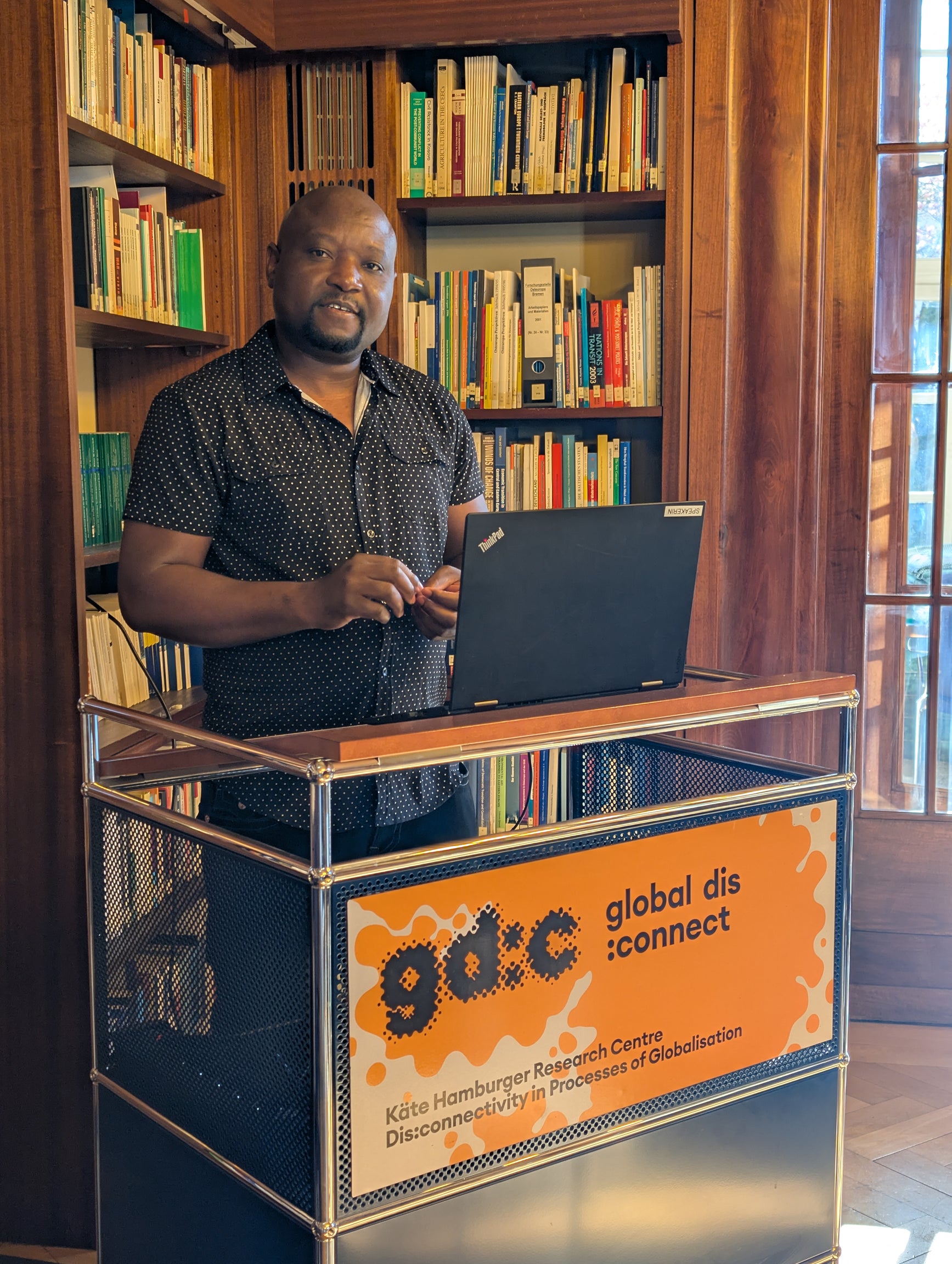

Barnabas Ticha Muvhuti, Nancy and Robert J. Carney Postdoctoral Associate in Art History at Rice, jetted to Munich last week to present at the “Dis:connected artistic belonging and recognition” workshop where he delivered his talk “Job Kekana: Taking the unfamiliar route and thriving on the periphery.”

“Art history is increasingly paying attention to dis:connectivities of transnational artistic trajectories and their roles in shaping multiple modernities. The two-day workshop interrogated which historiographic narratives artists on the move get inscribed into, juxtaposing these narratives with the artists’ own perceptions of professional belonging and recognition. Presenters examined whether such a move constitutes a detour in the artists’ life and career, in that it diverts a (personal or professional) trajectory, and how the move and new place of creation affects the artist’s career and inscription into institutional, art historical and hegemonic narratives. The workshop was especially interested in artists who went to places outside well-established centres of modernity.”

“Job Kekana: Taking the unfamiliar route and thriving on the periphery”:

When South African artist Job Kekana (1916-1995) crossed the Limpopo River heading to the North in 1944, his was an unfamiliar journey of uncertainty, yet unique when compared to that of fellow contemporaries like Ernest Mancoba and Gerard Sekoto who found home in Paris – an undisputed cultural capital at the time. In Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) Kekana settled at St Faith’s Mission, an Anglican Church institution situated on a farm on the fringes of Rusape, about 170 kilometres from Salisbury, the country’s capital city which was cosmopolitan, albeit arranged along segregated lines and communities, with the minority colonial settlers living the best life. A decade after his arrival, Kekana was commissioned to carve the ceremonial mace for the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland in 1954, an opportunity accorded to a recognizable artist in the land. In 1960, after the Rhodesian administration granted him a passport, Kekana received funding from the Beit Trust, which enabled him to go to England where he enrolled at Sir John Cass School of Art for three years. At the end of his studies, he headed back to Rhodesia, going back to St Faith’s Mission. In the mid-1960s, Kekana founded the Kekana School of Art and Craft. Among the most prominent students of his were David Chituku, Barnabas Ndudzo and Guy Mutasa. This paper examines Kekana’s move to the colony of Rhodesia, taking note of his breakthrough against the odds. Through the views of community elders like VaMaibvisira – the headman of the Madetere local village, Mbuya Gwatidzo – one of the village’s most senior members, and VaMukoyi – the former headmaster of St Faith’s High School, the author explains how and why Kekana thrived at the missionary station against the odds. Coming from a different country and culture, and belonging to a different ethnic group, speaking a different language, the paper grapples with Kekana’s smooth integration into the community, and its overall impact on his career.